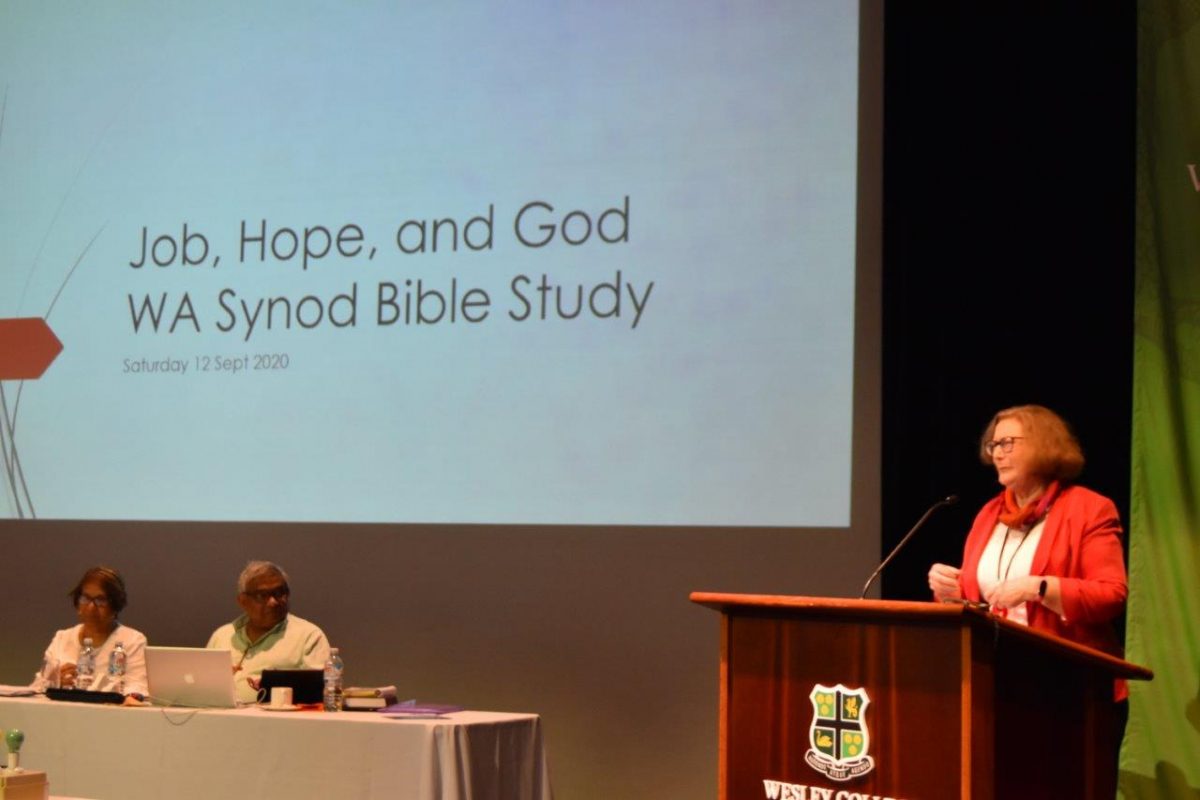

Rev Dr Christine Sorensen, Presbytery Minister (Formation and Discipleship) for the Uniting Church WA, shared Bible studies at the 44th Annual Meeting of the Synod of WA, on both Saturday and Sunday. She shared her studies on the book of Job, within the theme of Overflowing with Hope.

On Saturday, Christine explored the kinds of images of God Job and his friends had, how that influenced the hope they held, and looked into what might shed light on our own hopes.

“What I hope for us to think about is how the ways that we conceive of God – the images that we have of God – affect the ways that we can hold on to hope in this world,” Christine said.

“The question for me that has arisen as I’ve read and studied is: Do the understanding or images of God we have affect the kind of hope we have? That is, we speak and say ‘hope in God’ – yet who the God is that we hope in?”

Christine said that in the beginning of the chapter, Job is a reverent follower of God. But by the end of Chapter 2, Job has lost his children, his wealth, his health, and social standing.

“The book of Job moves into the poetic dialogues at this point, and Job explodes in grief, and cries out for justice and his friends respond,” she said.

Job’s friends believe in a God of reward and retribution; and they begin to accuse Job of being punished by God for his sinful behaviour.

“The wisdom that Job’s friends Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar offer is traditional. Repentance would bring God’s mercy and restoration,” Christine said.

Job, who knows he is innocent, struggles with this belief of God that his friends hold. Job starts to question: if he is innocent, then is God unjust?

Christine said that Job, unlike his friends, has an intimate relationship with God.

“When God responds to Job, we have not an image of God, but God-self. God who shows immense power of that elemental life force; Job’s God, a personal God; God who is free and creative, not limited to dualistic, right-wrong and reward-retribution ways of understanding the world.

“How do our images of God challenge hope? The limiting frame of the friends, and even of Job, stop them from hoping ‘outside of the box’. God challenged those images even as we are still challenged.”

As she closed her session, Christine invited Synod members to discuss in their table groups the main images of God they hold in their hearts that guide their hope.

On Sunday, Christine talked about what Job hoped for, and how that might help us in how we shape and live out our own hope. She explained that hope is not the same as optimism.

Job, Christine said, hopes for death and then for vindication. But this too is challenging for Job, as he realises death will grant him an end to the pain of life, but it won’t deal with his bigger problem of the loss of God.

“His life has been upended: his children are dead, his wealth vanished, his health turned to sickness, and his standing as a man of honour turned to derision. His life is misery.

“But there is more: Job has lost God. Job feels abandoned by God. So Job wants to die.”

Christine added that while Job hoped for death, he never actually considered taking his own life.

“While death is an intense desire, it is something that Job still sees God responsible for. That is – the psychology of hope paradigm pinpoints Job’s hopelessness – he has a hope but no way of getting there, and in fact it will not serve his real goal. So Job’s hope for death becomes hopelessness.

“In the midst of this struggle, and Job’s abandonment of the hope for death, there is a glimpse of a different hope – a hope that God still is, God is in the deep blackness, still there and active, even if it were to bring death, and that Job clings on to some vestige of his hope in God. Even in hoping for death.

“That gives me hope. I think it gives Job hope.”

Christine invited those present to discuss in pairs what has held them when they felt like they wanted their pain to be over.

She then discussed Job’s hope for vindication.

“Job moves away from the hopelessness of hoping for death toward hoping to be judged right. He plans to defend himself before God, as it were, to bring a court case, and be found not-guilty.

“From a hope psychology perspective, Job is doing well in his hope: Job has personal agency – he speaks about how he will search for God, deliver a summons, and petition God, even if he is a bit unclear about where he is going to go.”

But, Christine explained, God does not accuse or absolve Job of anything, but makes it clear the case will not be decided on Job’s terms.

“Job drops his case against God. Job knows himself to be vindicated – but not in the terms that he has planned to put forward.

“Vindication is part of the mindset which seeks blessing for faithfulness, and so needs to be deemed innocent to gain the reward. That is not ultimately how God works.”

Christine said vindication as a hope is vain, because Job didn’t need it, and vindication is about ourselves and not about God.

“Vindication is vain because our love of vindication means we want to hang on to our plans, our visions, our projects, all that is ‘us’ rather than that which is open to the majesty of God, who is way beyond our ways of thinking.

“So, in the end what does Job really hope for?

“He hopes desperately for God – for relationship with God; for the care he has known of God; and even for God not to be seen as unjust.”

As she concluded, Christine invited members to ponder some questions about hope:

What concepts of God do we carry with us that affect our hope?

What hopes of death may we need to lay aside?

What hopes for vindication may we need to let drop?

What passion for God – to know God more deeply ourselves and want our world to know the grace and hope in Jesus Christ that we have?

Have you struggled to keep a passion for God alive in the midst of whatever your life and ministry is?